What a long, long month September 2014 has been - and yet we still have a couple of days of it left! During this time I have been to two job interviews, been given one job, had to give it up to start the other and of course been as fully involved in the last two weeks of campaigning including one trip to a border tea party in Berwick as well as helping out at street stalls and then back to Newton Stewart for the big vote itself. Followed by great disappointment but then the renewed determination of the great defeated. It has been a dramatic, highly charged few weeks.

We came very close to winning a Yes vote in the independence referendum with 45%. Only another 200,000 of the swing voters who eventually went for a No vote could have been enough to win it for the Yes campaign albeit by a very slim majority. In the most deprived areas of Scotland we achieved our highest vote - Glasgow, Dundee, West Dunbartonshire and North Lanarkshire. This could only have been testament to the great work put in by the Radical Independence Campaign which made sure people realised this was a huge opportunity for change. But I believe that threats made by big banks and businesses, threats they didn't need to make and threats given extensive coverage by the mainstream media lost it for us.

However dejected we feel about the result, the fact that the Yes campaign grew support for independence substantially is a huge achievement. We were always the underdogs, yet in Glasgow we polled in a majority of those who turned out to vote. I will always feel proud of Glasgow for that support despite the Daily Record being so against independence. The ball is now firmly in Westminster's court, they have to deliver or face a loss in support for the Union - and the politicians down there clearly realise that. As the 45% we can help make sure they are fully held to account for what they do and don't deliver in the way of enhanced devolution.

It is hard to say if we made any mistakes in our campaigning, we could only really do our best but we certainly proved we were capable of doing our best. I think next time we will definitely need a bolder vision of independence because on certain issues we were ridiculed for not going all out in a break from the UK. Most notably was the question of currency. The SNP's preferred option of keeping the Pound Sterling put us at the mercy of Westminster who could and did say no to a currency union. And the Unionist politicians were able to use to Pound as a pawn in the argument in such a way that it was as though Scotland needed the English balance of payments into the Pound rather than the other way round. If England, Wales and Northern Ireland didn't sign up to a currency Union they would lose a important contrituion to their own currency by Scotland not being part of it and then they would have to pay all of the UK debt because they are legally responsible for it. In other words it would be the rUK, rather than Scotland, that loses out as a consequence of no currency union taking place. The pound would weaken without oil and other exports being a part of the economy. A separate Scottish currency would certainly be a strong currency as Jim Sillars has pointed out. So my view is that next time, we go the whole way and argue that an independent Scotland should use its own currency. This would put Scotland in a far better negotiating position at a future independence negotiations with Westminster.

I also think we made a few other mistakes in our arguments mostly where we were seemingly trying to soften the blow of independence. One of them was the idea that 'we're not really leaving the United Kingdom, because we'll still be part of a united kingdom with the Queen as head of state.' I don't think this was a very wise argument. The United Kingdom is a clear concept that refers to a particular sovereign state as governed currently from Westminster rather than all the countries with the Queen as head of state. Otherwise we might as well regard Australia, Canada and New Zealand as 'part of the UK.' If people say they 'like the idea of being part of the UK' then we have to challenge why they like it and why they wish to be part of the UK when it is as it is a state that doesn't work for everyone. For many of them its simply personal, a sort of nationalism, so we can't really do anything about that. But if they say 'we like Scotland being British' you have to challenge them as to what they mean by 'being British'. Why do we need to share a common sovereign state to feel like our fellow citizens and family south of the border are still very much are fellow citizens and family? And why should British only be the adjective for the UK when it is also thought by many to simply be the adjective of a place called Britain regardless of whether that's the UK or Great Britain. It's just those two definitions become unpegged with Scottish independence. I should say however that being British 'because we're part of the British Isles' is not a very good argument either because the name British Isles is contentious in the Republic of Ireland where there is no basis either political (UK) or geographical (Great Britain) for being considered British. I for one believe 'the Anglo-Celtic Isles' would be a better name for these isles where it lacks a rather imperialist set of connotations and seems more appreciative of different cultures within the isles.

Similarly I think we should have been willing to accept Scotland as a secessionist country rather than a co-continuation of the UK. I can understand the co-continuation argument but I think it reasonable for people in England, Wales and Northern Ireland to feel that their own countries would form the outright continuation the UK in the eyes of the international community. The principle of co-continuation would mean we automatically remained part of the EU instead of having to reapply. But soon that principle could be unnecessary as the UK leaves the EU and so in any circumstance Scotland would have to reapply. We should be able to wholeheartedly embrace the idea of a new sovereign state emerge with an institutional blank canvas to paint up our own new internationalist society. Let South Britain and Northern Ireland be the continuation of the UK, we have our own agenda up here. UK is not OK.

It has been the most fantastic and unexpected response from 45% who didn't win that the SNP has suddenly enjoyed a sharp rise in membership numbers with people turning to Alex Salmond and Nicola Sturgeon's party from often socialist backgrounds. This gives the SNP fresh blood that could help move the party in a direction towards a more radical vision of independence. I certainly hope that very soon we could see a revote on NATO which would overturn the prospect of joining such a controversial organisation. A reenergised SNP should also see a discussion had between radicals and moderates in the party about the what approach to taxation is the best to ensure Scotland is both a successful economy and a progressive society. Add to that the promise of a referendum on the monarchy and the thought of entering the European Union as our own state independent of a country that will probably be leaving it in 2017 and you have a very attractive vision of a new radical independent Scotland.

Monday, 29 September 2014

Saturday, 6 September 2014

The important difference between ethnicity, national identity, citizenship, residency and where you're born

For many people, it's nice and simple. You're born in a single country and in that same country, specifically the same region as your birth, you grew up, were educated and still live. Both your parents were born and grew up there as did many of their preceding generations. You therefore have the local accent and of course the citizenship of that country. You are quite unmistakably of that country specifically of that region.

But for many of us it really isn't as simple. Yours truly is a case in point. I was born in Oxford to an English mother and Norwegian father (whose father was Swedish). I grew up in a corner of southern Scotland called Galloway from the age of three, though spent some of my formative years in Penrith and the Eden Valley. That said my accent was the one my Mum and older siblings spoke, a southern English accent. I suppose that was awkward because everyone else in my class at Primary School had the local Scottish accent and even at school in the north of England my accent stood out no less. In relation to my father's side of the family, we regularly went on our summer holidays to Scandinavia to our cottage in Sweden where we saw all of my father's family and that helped reinforce my sense of being part Scandinavian.

I'm not Scottish. I do not consider myself to be Scottish. I still live in Scotland but what I am in terms of national identity is quite different to where I call my home. Because national identity is an aspect of personal description while my home is a matter of location and where I feel I belong. So while my home is Scotland, I am English. My national identity relates to my parents' backgrounds and I have identified one of those backgrounds as my primary nationality, the one I give if I can only state one or only feel like stating one. That primary nationality is for me determined through a stronger sense of association with that background than the other. If I had grown up anywhere in Scandinavia speaking their language I probably would have given my identity as Norwegian so in some respects my upbringing does determine my primary nationality in terms of choosing between English and Norwegian. But I grew up on the west side of the North Sea speaking English as a first and only fluent language meaning I felt more English than Norwegian. So ironically I'm English because I grew up in Scotland. Strange isn't it?

I don't particularly like the word 'national identity' used for individual people. It's supposed to be a collective thing - the national identity of Scotland is about an overall image and character of a nation. But people within any nation are highly diverse culturally and you can get someone born and bred in Edinburgh who has more in common socially and culturally with somebody from Auckland, New Zealand than someone living just next door. When I say "my national identity is English", it is merely a statement of my association with the country of England than me being a microcosm of the English national character, whatever that might be. Still the term 'national identity' is a word used on individual basis' so I guess I will have to use it. So my national identity is English. Or to be more precise I am English first. Then I am Norwegian and then I am Swedish. And distantly I am equally Scottish and Irish but I have little knowledge of the ancestors they refer to so I don't really feel they're part of my national identity.

This is why I objected to one particular Unionist complaint. When a couple of years ago they started going on about a supposed false choice between Scottish and British I did a bit of google research to investigate the origin of the complaint. Blow me - the offending question about ethnicity drafted in 2008 for the Scottish Government's 2011 census. The multiple choices included Scottish, English, Welsh, Irish, British and so on and you could only choose one. You also had an 'Other' box with a space to write in the term you use to describe your ethnicity. The cause of offence was that if you stated Scottish you were saying you were not British. But this was to misunderstand the question. It asked you which best describes you ethnicity. Not your national identity but your ethnicity. Many people who are Scottish in all lines going back several generations would have chosen 'Scottish' because they don't know of any other ethnicities in their background but people who tick British do so usually because a number of their family lines are also ethnically English, Welsh, Irish or a mixture so the word British is used as a means of combining them all. The reaction from the unionists seemed to suggest people should have be an additional 'Scottish and British choice'. For one thing this would betray many people's feeling that to say you're Scottish is to actually say you're British. A lot of people in England feel that stating you're 'English' is stating you're 'British' because quite simply England is a nation of Britain. Likewise with Scotland. The suggestion was that people on either side on the constitutional divide are somehow divided by ethnicity. Such a suggestion would be both unwise and absurd because ethnicity is nothing to do with political preferences. Lets just for argument's sake take the Proclaimer twins. Imagine Craig Reid converted to being pro-union while Charlie Reid stayed firmly in the pro-independence camp. Does Craig Reid suddenly have a different ethnic background to the very person with whom he shared the same zygote? I think not.

Now for nationality, the official kind, that is to say citizenship. Yes in case you haven't realised there's a difference between nationality and nationality. Two definitions of nationality, one being official (citizenship), the other being unofficial (national identity) and often based on the subjective. I would gladly take up Scottish citizenship but that wouldn't make me Scottish by the concept of national identity that I explored in an earlier paragraph. My national backgrounds would continue to be English, Norwegian and Swedish. But I would now be a citizen of the Scottish state and so would be officially saying I have trust in that state to look after me. It will be a much more notable statement when, despite being allowed to keep British citizenship in duality with Scottish citizenship, I renounce British citizenship in favour of just Scottish citizenship. I haven't yet decided if I'll actually do that but I'll think about it. But I can tell you that despite all my pride in my Norwegian heritage I'm absolutely glad I never held Norwegian citizenship. If I had done so I would have been required to do national service at the age of 18. No way would I have wanted that! So for me citizenship is about the sovereign state to which I choose to belong and be protected by.

Residency is about where I live and is an unofficial kind of citizenship. Because there is no such thing currently as Scottish citizenship the franchise of a referendum in Scotland can only pragmatically be determined as the people living there and therefore making the most directly contribution to the Scottish economy and Scottish society. So a Scottish resident may or may not be Scottish by origins or self-identification but he or she is considered one of the Scottish people when it comes to determining Scotland's future.

Where you're born? That's surely the easiest thing to understand. But the country of your birth could be anywhere, you could be born when your parents are on holiday abroad for example. Many people feel a certain bond with the country of their birth regardless of its relevance or irrelevance to their parents' national backgrounds. If I had been born in say, Yemen, I may have been tempted to have describe myself as Yemeni for the novelty factor. Incidentally someone who was born in Yemen was Eddie Izzard although he would generally describe himself as English. Still I think many people would make a case for the entitlement to citizenship of the country of your birth if you choose since it is listed on your own passport and birth certificate and if you're born in 'Yemen' you're 'born Yemeni'. Fortunately for me I don't have that confusion, I was born in England so my primary nationality is also my birth nationality.

As for the question 'Where do you come from?' for me that is a bit ambiguous. Are they asking me my nationality (national identity) or my country of residence? Well if I'm being asked that question in my country of residence, Scotland, I would usually say something, South-west Scotland, Dumfries and Galloway or Newton Stewart, depending on how well they might know the places around Scotland. However, they may enquire further about my accent so I would mention that my family are from Oxford originally. If I'm somewhere abroad, like Italy, India or somewhere else where they're quite chatty and I'm asked the question of where I come from then my simple answer would be 'Scotland'. What they're interested in knowing is the country where I live for most of the year, the country which was the starting point of my journey to that destination where I'm talking to these very friendly people. They want to know about where you live because that's the place you know the best, that's your home. If however I'm being asked what my nationality is, well that's different, then I say 'I'm English' because they're asking me about my national description not about where I live. But normally the people I get talking to ask me where I come from so that's okay.

So there you have it - the difference between birth, ethnicity, nationality and so on. They are all different ideas, each with their own meaning. And for people like me their descriptions are hugely mixed up but the more I explore them the more I understand what's what. Is there anything in there that's a source of pride for me? Not really. Except for my Scandinavian heritage because that means I've had somewhere truly wonderful to visit during Summer holidays. And I also like the fact that my English Great-Grandfather drove the Flying Scotsman (though only from London to York). I feel privileged to have lived in Scotland most of my life and now I feel a I have a massive chance to help shape that nation's future and determine the sort of place it becomes. But different aspects of my personal description I treat as individual subjects which may or may not be relevant to a debate about a country of 5.3 million people and therefore 5.3 million different identities.

But for many of us it really isn't as simple. Yours truly is a case in point. I was born in Oxford to an English mother and Norwegian father (whose father was Swedish). I grew up in a corner of southern Scotland called Galloway from the age of three, though spent some of my formative years in Penrith and the Eden Valley. That said my accent was the one my Mum and older siblings spoke, a southern English accent. I suppose that was awkward because everyone else in my class at Primary School had the local Scottish accent and even at school in the north of England my accent stood out no less. In relation to my father's side of the family, we regularly went on our summer holidays to Scandinavia to our cottage in Sweden where we saw all of my father's family and that helped reinforce my sense of being part Scandinavian.

A cottage in Sweden reminiscent of summer holidays

I'm not Scottish. I do not consider myself to be Scottish. I still live in Scotland but what I am in terms of national identity is quite different to where I call my home. Because national identity is an aspect of personal description while my home is a matter of location and where I feel I belong. So while my home is Scotland, I am English. My national identity relates to my parents' backgrounds and I have identified one of those backgrounds as my primary nationality, the one I give if I can only state one or only feel like stating one. That primary nationality is for me determined through a stronger sense of association with that background than the other. If I had grown up anywhere in Scandinavia speaking their language I probably would have given my identity as Norwegian so in some respects my upbringing does determine my primary nationality in terms of choosing between English and Norwegian. But I grew up on the west side of the North Sea speaking English as a first and only fluent language meaning I felt more English than Norwegian. So ironically I'm English because I grew up in Scotland. Strange isn't it?

I don't particularly like the word 'national identity' used for individual people. It's supposed to be a collective thing - the national identity of Scotland is about an overall image and character of a nation. But people within any nation are highly diverse culturally and you can get someone born and bred in Edinburgh who has more in common socially and culturally with somebody from Auckland, New Zealand than someone living just next door. When I say "my national identity is English", it is merely a statement of my association with the country of England than me being a microcosm of the English national character, whatever that might be. Still the term 'national identity' is a word used on individual basis' so I guess I will have to use it. So my national identity is English. Or to be more precise I am English first. Then I am Norwegian and then I am Swedish. And distantly I am equally Scottish and Irish but I have little knowledge of the ancestors they refer to so I don't really feel they're part of my national identity.

The border between England and Scotland. I grew up in both Galloway and Cumbria.

Ethnicity is deeper than that. It is about race, genetics, skin colour and so on. This is when I do take into account more distant generations. Broadly I am white Caucasian. Specifically I describe my ethnicity as Nordic Anglo-Celtic, in other words, Northern European. My ethnicity split on this side of the North Sea, Anglo-Celtic, considers the fact that as well as being English, there is also I understand traces of Welsh along with my Scottish and Irish roots. Nordic takes into account ancestry from any of the Nordic countries, not just Scandinavia. It is also thought that I have some distant Russian ancestry because of my nose and cheekbones!This is why I objected to one particular Unionist complaint. When a couple of years ago they started going on about a supposed false choice between Scottish and British I did a bit of google research to investigate the origin of the complaint. Blow me - the offending question about ethnicity drafted in 2008 for the Scottish Government's 2011 census. The multiple choices included Scottish, English, Welsh, Irish, British and so on and you could only choose one. You also had an 'Other' box with a space to write in the term you use to describe your ethnicity. The cause of offence was that if you stated Scottish you were saying you were not British. But this was to misunderstand the question. It asked you which best describes you ethnicity. Not your national identity but your ethnicity. Many people who are Scottish in all lines going back several generations would have chosen 'Scottish' because they don't know of any other ethnicities in their background but people who tick British do so usually because a number of their family lines are also ethnically English, Welsh, Irish or a mixture so the word British is used as a means of combining them all. The reaction from the unionists seemed to suggest people should have be an additional 'Scottish and British choice'. For one thing this would betray many people's feeling that to say you're Scottish is to actually say you're British. A lot of people in England feel that stating you're 'English' is stating you're 'British' because quite simply England is a nation of Britain. Likewise with Scotland. The suggestion was that people on either side on the constitutional divide are somehow divided by ethnicity. Such a suggestion would be both unwise and absurd because ethnicity is nothing to do with political preferences. Lets just for argument's sake take the Proclaimer twins. Imagine Craig Reid converted to being pro-union while Charlie Reid stayed firmly in the pro-independence camp. Does Craig Reid suddenly have a different ethnic background to the very person with whom he shared the same zygote? I think not.

Now for nationality, the official kind, that is to say citizenship. Yes in case you haven't realised there's a difference between nationality and nationality. Two definitions of nationality, one being official (citizenship), the other being unofficial (national identity) and often based on the subjective. I would gladly take up Scottish citizenship but that wouldn't make me Scottish by the concept of national identity that I explored in an earlier paragraph. My national backgrounds would continue to be English, Norwegian and Swedish. But I would now be a citizen of the Scottish state and so would be officially saying I have trust in that state to look after me. It will be a much more notable statement when, despite being allowed to keep British citizenship in duality with Scottish citizenship, I renounce British citizenship in favour of just Scottish citizenship. I haven't yet decided if I'll actually do that but I'll think about it. But I can tell you that despite all my pride in my Norwegian heritage I'm absolutely glad I never held Norwegian citizenship. If I had done so I would have been required to do national service at the age of 18. No way would I have wanted that! So for me citizenship is about the sovereign state to which I choose to belong and be protected by.

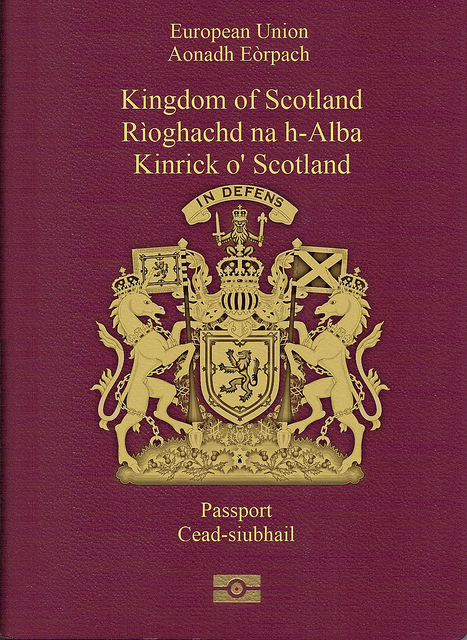

A Scottish Passport as it might look. This is something I look forward to owning one day.

Residency is about where I live and is an unofficial kind of citizenship. Because there is no such thing currently as Scottish citizenship the franchise of a referendum in Scotland can only pragmatically be determined as the people living there and therefore making the most directly contribution to the Scottish economy and Scottish society. So a Scottish resident may or may not be Scottish by origins or self-identification but he or she is considered one of the Scottish people when it comes to determining Scotland's future.

Where you're born? That's surely the easiest thing to understand. But the country of your birth could be anywhere, you could be born when your parents are on holiday abroad for example. Many people feel a certain bond with the country of their birth regardless of its relevance or irrelevance to their parents' national backgrounds. If I had been born in say, Yemen, I may have been tempted to have describe myself as Yemeni for the novelty factor. Incidentally someone who was born in Yemen was Eddie Izzard although he would generally describe himself as English. Still I think many people would make a case for the entitlement to citizenship of the country of your birth if you choose since it is listed on your own passport and birth certificate and if you're born in 'Yemen' you're 'born Yemeni'. Fortunately for me I don't have that confusion, I was born in England so my primary nationality is also my birth nationality.

As for the question 'Where do you come from?' for me that is a bit ambiguous. Are they asking me my nationality (national identity) or my country of residence? Well if I'm being asked that question in my country of residence, Scotland, I would usually say something, South-west Scotland, Dumfries and Galloway or Newton Stewart, depending on how well they might know the places around Scotland. However, they may enquire further about my accent so I would mention that my family are from Oxford originally. If I'm somewhere abroad, like Italy, India or somewhere else where they're quite chatty and I'm asked the question of where I come from then my simple answer would be 'Scotland'. What they're interested in knowing is the country where I live for most of the year, the country which was the starting point of my journey to that destination where I'm talking to these very friendly people. They want to know about where you live because that's the place you know the best, that's your home. If however I'm being asked what my nationality is, well that's different, then I say 'I'm English' because they're asking me about my national description not about where I live. But normally the people I get talking to ask me where I come from so that's okay.

Oxford, where I was born

So there you have it - the difference between birth, ethnicity, nationality and so on. They are all different ideas, each with their own meaning. And for people like me their descriptions are hugely mixed up but the more I explore them the more I understand what's what. Is there anything in there that's a source of pride for me? Not really. Except for my Scandinavian heritage because that means I've had somewhere truly wonderful to visit during Summer holidays. And I also like the fact that my English Great-Grandfather drove the Flying Scotsman (though only from London to York). I feel privileged to have lived in Scotland most of my life and now I feel a I have a massive chance to help shape that nation's future and determine the sort of place it becomes. But different aspects of my personal description I treat as individual subjects which may or may not be relevant to a debate about a country of 5.3 million people and therefore 5.3 million different identities.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)